Tempo 2.0 - Section 3.3 Value Streams and Process Flows

…that the greatest prosperity can exist only as the result of the greatest possible productivity of the men and machines of the establishments— that is, when each man and each machine are turning out the largest possible output.

— The Principles of Scientific Management, by Frederick Taylor, 1911.

The 20th century was a century of economic growth and technological development never seen before in the history of humanity. A significant part of the credit for this has to go to Frederick Taylor, whose book The Principles of Scientific Management, was published in 1911.

Taylor laid down the basic principles of mass production. The ideas worked well for many years, but there were hidden problems.

One thing that happened, because the idea was that each worker and each machine should produce as much as possible as much of the time as possible, was that parts tended to pile up, everywhere. Different people, and different machines, doing different things, produce things at different rates. If you produce a lot of different parts that will eventually be fitted together, you will inevitably end up with too many parts of some things, and too few of other things.

Having big piles of unused parts laying around didn’t bother people much in the early 20th century. One reason was that the economy overall was expanding, except for the occasional depression, and most of the time, the parts in those big piles would eventually be used and sold. Another reason was that the prevalent accounting model, Cost Accounting[Cost Accounting is still the prevalent accounting model. It is still a model with problems, but today there are several alternatives, who have their own pros and cons.], regarded those big piles as assets. At the time, it was a reasonable assumption that whatever you produced would eventually be sold.

“Reasonable” does not always mean correct. Those piles of parts were actually a huge risk. Having capital tied up in parts meant a company had less cash on hand. If something happened, like a depression, or just a change in what the market wanted, the parts might become worthless, and the company stuck with them would suffer a huge loss.

Using an inherently wasteful production system also meant huge economic barriers to entry for new companies…unless someone could figure out how to make a small number of products with a much smaller investment.

Eventually, someone did.

The quality guru W. Edwards Deming is considered one of the greatest management experts of the 20th century. Deming traveled from the US to Japan in the early 1950’s. He taught both managers and engineers statistical methods to improve quality. However, there was something that Deming considered even more important.

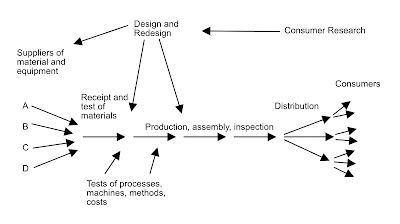

Deming taught how to view a company, and the environment it operates in, as a system. He summarized what he taught in a simple sketch.

Figure: Deming’s view of manufacturing organizations as systems.

Deming’s simple sketch was the start of a revolution. Deming described a flow of materials, a value stream. He also described feedback. Information is retrieved from customers, and fed back into the process.

In 1950 Japan was a country in a deep economic crisis. The industry was obliterated during World War II. Nobody knew how to rebuild the country again.

Deming’s sketch held the key to the Japanese economic miracle. In the West, mass production based on Frederick Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management reigned supreme. There was no way that a poor country like Japan could make the investments necessary to build an industry based on mass production.

The Japanese decided to change the rules, and play a different game. They would outmaneuver their stronger opponents. While Western companies were built around the functions needed for manufacturing, Japanese companies like Toyota and Honda decided to organize around the process flows companies need.

Value Stream became a central concept. The idea was to look at value streams from the perspective of the customer:

What does the customer want to get out of the process?

Looking at the process flow, the value stream, from the perspective of the customer made it possible to divide the flow into value adding time and non-value adding time. An astonishing discovery was that in most processes, only a small part of the time was value adding time. Most of the process time was non-value adding time, and the Japanese companies worked hard to get rid of it.

Getting rid of non-value adding time made it possible to produce things in much smaller volumes than mass production systems, with much smaller investments, and still make a profit. The feedback loop from customers meant that initially shoddy products would be improved over time. Eventually, they became good enough to turn quality into an additional competitive advantage.

Deming’s sketch represents the smartest business strategic move of the 20th century. To be clear, Deming did not, on his own, save Japan’s industry. Nor was he the only one who had bright ideas. The Japanese economic miracle was a lot more complex than that. Still, Deming’s sketch sums up the basic idea in a way that is easy to understand, even if it is a challenge to implement it.

In the West, we never really got it. For a long time, we continued to base our industry on the outdated mass production model. Scientific Management is so integral to how we think that most people who use it don’t even know its name. It’s the only way we know, so there is no need to distinguish it from anything else.

Our terminology has changed. Talking about value streams is popular today, but if you look closely at organizations and processes, they are often built around the old way of thinking. Many companies have redesigned their factories, but even then, the administrative processes, distribution networks, and management paradigms, are often based on Taylor’s ideas.

In the same manner, there is a lot of talk about the “customer”, but what is meant is often the next step in the value stream, not the customer who will use the product or service. This twists the whole idea of thinking in terms of value streams.

The tendency to adopt new terminology, without really changing anything, means a lot of good opportunities are lost. The purpose of this book is not to convince you that any particular idea is better than everything else. I do want you to appreciate the importance of new ideas, and I want to emphasize the importance of understanding ideas, rather than blindly following recipes. The reason is that implementing a good idea requires adapting it to your situation. To do that, you need to understand both the idea, and your situation. Blindly following a recipe for success, is actually a recipe for failure.

Takeaways

- Optimizing each part of a process often leads to sub-optimization of the whole.

- If you do not know which management paradigm you are using, you are almost certainly using Scientific Management.

- Scientific Management will get you, and your company into trouble, unless you have a deep understanding of its merits and limitations. It is safest to assume that you don’t.

- Understanding value streams is a key to understanding production systems. Do not make the mistake of believing it is the only key!

- Building organizations around value streams makes it easier to optimize processes than building organizations around functions.

- Process flows can be divided into value added time and non-value added time. Non-value added time is bad, so try to get rid of it.

- The customer is the user of the product, not someone in the production process.

- Adopting value stream terminology does not make your organization focused on value streams. Building, or rebuilding, your organization around value streams does…but watch out for innovative ways of screwing things up.

- Learn to appreciate the value of new ideas, but don’t be so open to new ideas that your brain falls out.

- Implementing ideas requires adapting them to your situation, and that requires understanding both the ideas and your situation.

- Following recipes for success, is a recipe for failure.

Comments